ETCHED IN MY MIND

After briefly looking over a photocopied conceptual sketch of a Paris Mountain residence designed by CGD’s co-founder and part namesake, Earle Gaulden circles back to it half an hour later, right when we thought our conversation with him was concluding. He handles the piece of paper in a manner that projects one part nostalgia, one part agitation. He then explains how the floor framing of the house cantilevers over the foundation wall for the entirety of its perimeter to give it the effect of lightness and suspension, much like the morning fog that often rests just over Greenville’s iconic monadnock. He suggests his handling of the condition was adequate but acknowledges he has thought of other ways to approach the detail and speculates concern over its ‘staying power’. “I’d like to drive up there and see it.” The astounding thing is that this is not supposition over a project under construction or recently completed. It was one of the firm’s first projects – completed in 1958. When offered the sketch, Earle defers. “No, I have the entire project etched in my mind.” As Earle Gaulden approaches his 90th year of life, it is overwhelmingly evident that nearly a half century of our region’s design history is etched in detail in his mind, the result of a decades-long climb to execute cutting-edge design in South Carolina.

THE TRAILBLAZERS

Bringing the design sensibilities of the Bauhaus and Marcel Breuer not only to Greenville but also to towns like Honea Path and Six Mile was an effort never before attempted. “We were pushing a big load uphill to start this,” says Earle. He and classmate Kirk Craig recognized the challenge of starting such a practice in the Upstate, “because there were none.” But, validation of the effort came quickly, “when the first check came in. That was confirmation of what we were doing.” Earle went on to say, “We set out to blaze new trails if we could… when we started, there was no one in Greenville designing above the ordinary. Maybe we were naïve.” Speaking specifically to the design perceptions encountered in the Upstate, Earle says, “Ninety-five percent of the population thought that architecture is Georgian, and you have to either design Georgian or convince them you ought to do something else. We set out to conquer those prejudices. We didn’t get a lot of work at first because of it, but then we got over the hump. I’m not sure what the hump was. Maybe it was uphill the whole way to be honest.” Earle readily concurs with an edict Kirk made in a 1956 letter to him declaring, “we aren’t as interested in making a mint on this as we are in making a name.”

THE TECHNICAL MIND & THE LEGACY

“I wanted to study art – and there was no art school. That simple.” Such is Earle’s reasoning for pursuing a degree in Architecture at Clemson, a relatively short distance from his hometown of Laurens, SC. It was at Clemson that Earle and Kirk first met and formed a collegial bond that would nourish the idea of starting a firm in Greenville. Following Clemson, Earle spent a year in the Army then a year at Georgia Tech earning a Master of Architecture. Kirk attended Cornell then Harvard. Fulfilling a dream detailed and planned over close correspondence while apart, their paths again converged in 1957 when the two formed Craig and Gaulden Architects in Greenville.

Kirk was the designer and socialite; Earle was so much the technical mind that he filled the role of engineer on some of the firm’s early work. “When I went in to Architecture right out of school, I thought that architects had to be engineers to do the buildings. Well, I was surprised,” he confesses. Though that role was soon handled by consultants, Earle still points to jobs such as the Meyer house, an early 1960s contemporary home in Greenville for which he engineered each of the exposed wooden plate trusses. “I was more technical than Kirk…Kirk was flighty,” Earle quips. Kirk was also the one out on the street drumming up business while Earle kept his hands on the drafting board. “Kirk would come in and say, ‘We’ve got a project on Haywood Road,’ and I didn’t know where Haywood Road was then. There was no such thing.”

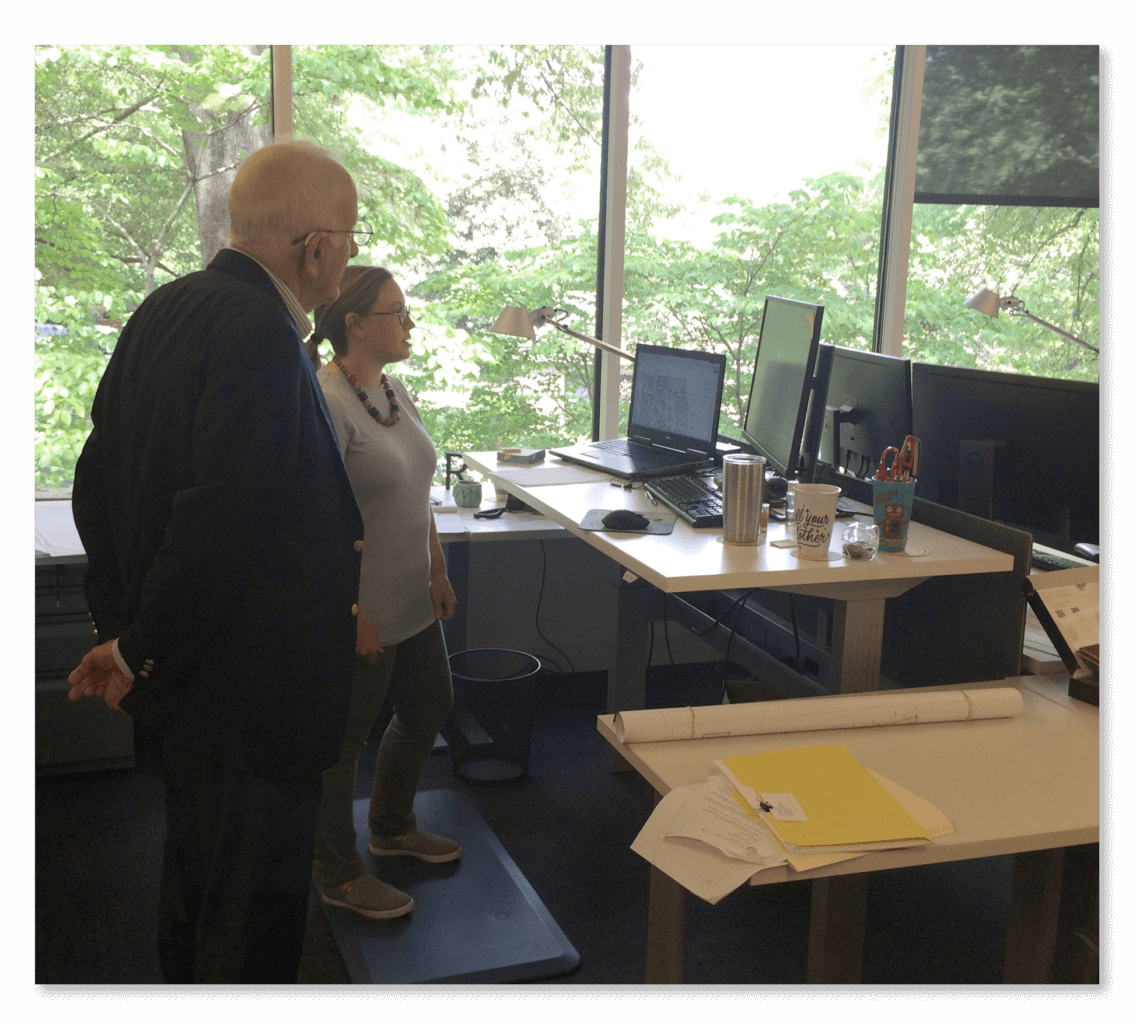

Earle and Rebecca talk Revit

Times have indisputably changed, but Craig Gaulden Davis and the timeless ambition of good and thoughtful design remains, following the aspirations of Kirk and Earle. “We had a wish to grow. That was one of our objectives. I guess it was two or three years we were knocking on doors, trying to get people to recognize us, and after that it was just nip and tuck every year to try and build a little bit more.” The growth of the firm both in size and reputation saw a steady increase over the decades with marquee projects along the way under Earle’s guidance: the Crosrol Carding building in the mid 1960s which still stands on Tower Road in Greenville, the Greenville County Museum of Art, the Little Theatre, the Peace Center. Between these major mile markers are countless CGD designed businesses, residences, libraries, and places of worship across the Upstate and the region.

Early in our discussion with Earle, he resignedly told us that although he does still occasionally critique a building when he walks by or into it, he no longer pulls out his pen and sketchpad, a ritual particularly associated with architects. Moments later, he grabbed the closest piece of paper and whipped out a mechanical pencil from his coat pocket to sketch a site map and a building parti. Over six decades after Earle first took out his drafting pencil as one half of Craig and Gaulden Architects, the same compulsion to always have our hands on our tools and our tools on our work as we endeavor to convey thoughtful and beautiful design solutions across the region still remains and propels us forward.

Among his many accomplishments, F. Earle Gaulden, FAIA was elevated to the American Institute of Architect’s College of Fellows in 1985 and awarded the Medal of Distinction by AIA South Carolina in 1995.

Contributed by Aaron Swiger