Kirk’s Paradigm says, for a great project you’ve gotta have the right owner, the right program, the right site, the right budget, the right contractor, and the right architect. If one of these is missing, the whole project can suffer for it. If you can get all six things to come together, then you have an opportunity to make something great.

Next up: Gotta Have the Right Budget!

Creating architecture is a complex process that involves many people and disciplines, committing to a particular goal, and, typically, a large investment. Budgeting is a reality and, arguably, the main reason to choose an architect you trust. As stewards of the investment portion, a budget must be created and kept in balance with the project scope and expectations of quality. The “Right” budget, as it relates to Kirk’s Paradigm, is one that fits the project. A small budget does not necessarily mean small aspirations (see Right Owner) or small solutions (Coming soon Right Architect), as long as the budget is aligned with the project goals.

Unlike most products or services for which one budgets, architecture cannot be bought-off-the-shelf or taken for a test drive. Architecture is the unique result of a design process, created for a specific purpose and built, one-of-a-kind, by a specially assembled team. Sometimes we don’t even know where the architecture will be (see Right Site) when it finally does exist. Because decisions made during the design phase come with either a price tag up front or as a later expense we’re taking a closer look at the variables.

U Pick Two

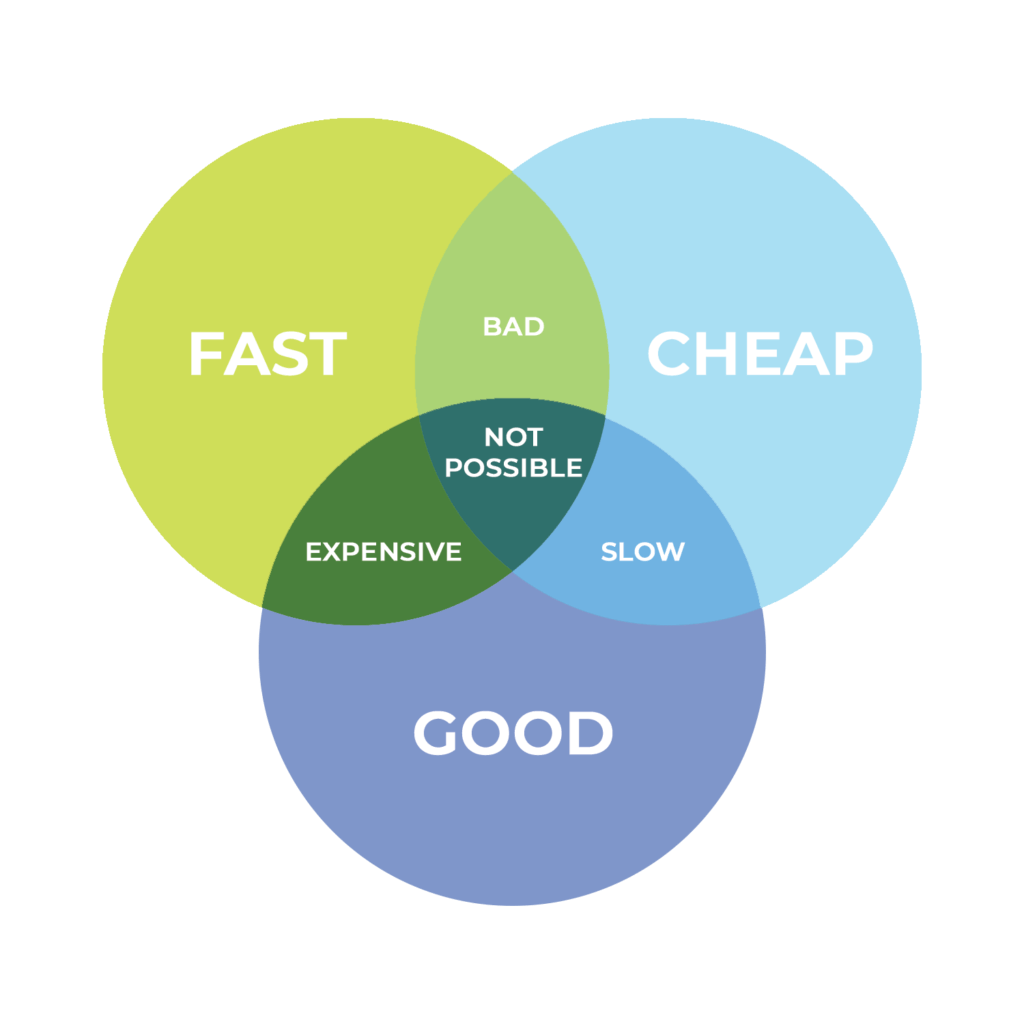

There’s an ‘old’ saying that, depending on where you hear it, goes something like “We provide our service fast, good or cheap. You can pick two.” The idea, of course, is that quality has a cost that we all recognize, and time is money. As visual thinkers, we can illustrate this reality with a Venn diagram showing three overlapping circular regions indicating “Good”, “Fast”, and “Cheap”. The central region common to all three is labeled with some variant of “impossible” “dreaming” or a unicorn.

There’s an ‘old’ saying that, depending on where you hear it, goes something like “We provide our service fast, good or cheap. You can pick two.” The idea, of course, is that quality has a cost that we all recognize, and time is money. As visual thinkers, we can illustrate this reality with a Venn diagram showing three overlapping circular regions indicating “Good”, “Fast”, and “Cheap”. The central region common to all three is labeled with some variant of “impossible” “dreaming” or a unicorn.

The ‘Pick Two’ reality applies to the end product as well as the design process itself, of which architectural services are a part. Throughout design, architects are helping make decisions that match the goals of the project considering all of the major components, design, construction time, materials, and cost.

Good architects choose materials, construction methods, and design details that achieve the proper balance of these elements. For instance, designing with pre-cast concrete wall panels is one solution that might seem more expensive than traditional masonry, however, it cuts construction time and those associated costs. The trade-offs involved with either method have to be reconciled with the project goals.

Another example, when working with institutional facilities that will be owned and operated for a very long period, the design must consider repairs and renovations over several generations. The higher first cost of quality materials, better insulation, or high-efficiency mechanical systems can be recouped by lower operating costs or longer in-service life of these better materials. One useful tool, Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCA), for long-term owners is key to understanding how construction budgets relate to the overall cost of building ownership and operations.

How, then, do we manage budgets?

Early and often. One of the most important tools we use is a project budget, which includes everything from land purchase and utilities to building cost, design fees, furnishings, equipment, and construction testing. We hire independent cost consultants to provide budget pricing. We believe in “healthy” design contingencies – not a design slush fund – that anticipates the evolution of design documents that are continually gaining in definition. A conceptual design estimate of construction cost might carry a 20% design contingency that will go down as the project variables of quality, scope, and expected delivery become defined. Initial conceptual budgets should also include “escalation”, an inflation factor recognizing that building projects sometimes take years to develop from ideas into realities. The long-term escalation trend is about 4% per year, even higher in economic expansions.

Another helpful measure is to design with discrete and well-defined alternates to deal with, presumably, fixed budgets in a variable construction bid market. Owners can “shell-in” space in the building for growth or future completion as funds allow. Forward-thinking design considers where utilities, machinery, and roof lines are best placed if additions are being considered for the future.

Speaking of the future

Building something that matters takes resources and we, as architects, are tasked with helping our owners be good stewards of their resources. Consider that what is good enough for now is not necessarily good for the future. When you build you are giving form to what you believe, which in turn will influence how you and others will live and work in the future. Let’s do our best to set everyone up for success.

Go to Part V of Kirk’s Paradigm: Gotta have the Right Contractor

Or head back to the beginning: Kirk’s Paradigm.

Kirk’s Paradigm is brought to you by Principal and project architect, Scott Simmons.